A Prologue of Sorts

So, the story began so -- Ever since my first visit to the Smithsonian National Postal Museum a few months ago, I have found postal history a marvelously captivating topic. Naturally it started with stamp collecting, which in my case involved buying packet after packet of random (and thankfully unsorted) American and foreign stamps from the Museum Shop. With it came hours of submerging stubborn stamps in plates of water, removing said stamps from the paper to which they were attached, drying them between sheets of paper, tucking them away into stockbooks and doing a bad job cataloging my unimpressive collection.

Like a rookie of any trade, my curiosity expands more horizontally than vertically, and I found myself reading about postmarks, precancels and overprints before even owning a magnifying glass (a cardinal sin, I trust, to any self-respecting collector, but I swear I do have a very good tweezer). More enthusiastically I browsed history of the United States Postal Service (USPS), and went as far as creating an account for Wikipedia just to expand the entry on Elaine Rawlinson, whose simple but dignified design of a 1938 stamp featuring George Washington came to define the famous "Presidential Series". Point is, I probably got a bit lost in the postal realm, and was looking for a better charted course.

Fortunately some postal pioneer has done pretty much all the charting. Devin Leonard's Neither Snow Nor Rain: A History of the United States Postal Service (a lovely read) began with the story of one Evan Kalish, who was on a crusade to visit as many post offices in the US as possible. At first I brushed it off as a fun anecdote, a feat impossible to emulate, until a few days ago. I was staring at a map of all post offices in the DC area, and was confused by the several "carrier annexes" that don't appear to be publicly accessible. A quick Google search brought me to, guess where, Mr. Kalish's blog Postlandia, and an article of his that answers perfectly my question.

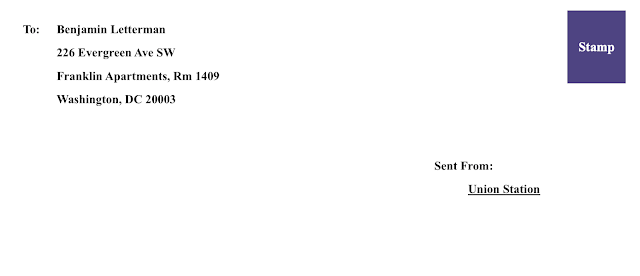

And so the stars aligned, prompting me to take advantage of the several weeks of semi-leisure ahead, and go on a postal pilgrimage of my own. I am to visit as many DC post offices as possible (provided that such does not interfere with my more important schedules), send a letter from each branch (hopefully with postmarks but only hopefully), and visit some other attractions along the way. Today was the day I set this plan in motion, and I thought I should write about it.

The National Capitol Branch

Equipped with three plain Caliber envelopes bearing my name, address, and the post office from which they were to be mailed, each carrying a slip of paper just for show (sending out empty envelopes felt like psychopathic behavior), I left home in early afternoon and headed straight to the Postal Museum -- more precisely USPS's National Capitol branch located in the same building. The Museum itself deserves a stand-alone article (or several), but the architecture warrants some mention here.

|

| A corner of the "New Post Office Building" built in 1914, now housing the Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Entrance to the National Capitol post office is seen to the left. |

Designed by Chicago architect

Daniel H. Burnham (who sadly did not live to witness its completion), the building was completed in 1914 and opened for business on Sept. 14. Its

Beaux Arts style closely approximates that of the Union Station, another brainchild of Burnham which had been completed seven years prior, and was quite a sight from afar. A lot of modern postal machinery was added to its interior in the mid-1950s, but the classical indoor decor continued to greet post-office-goers until 1971, when the magnificent ceiling was lowered, and marble walls lined by

Formica counters. Today the Museum still looks back at its modernization with embarrassment, calling its renovated lobby an "architectural eyesore to many" before concluding how "

modern doesn't always mean better".

Luckily, when mail volume in DC grew so large that not even this five-story behemoth could handle it, a new processing plant was built a few miles up north (now one of those carrier annexes that I should probably visit sometime) in 1986, and most postal operations were transferred there. With practicality no longer a concern, architects set out to convert the building back to its original state, and the Museum opened its doors on July 30, 1993. Some postal functions remained -- People of Judicial Square still needed to send letters and holiday greetings, after all -- but tucked away on the cavernous bottom floor, usually with more staff members than customers.

|

| Entrance to the post office |

Today I counted myself amongst said customers which, probably thanks to the Christmas-y spirit, numbered six or seven, surpassing the staff by three or four. I got myself twenty "snow globe" stamps, put one onto the envelope marked "National Capitol," and threw it into the collection box. A job well done.

But of course I could not walk away so nonchalantly without taking a few more looks around. There were a few enlarged stamp posters here and there, a shiny plaque dedicating this building "to public service" in 1992, but nothing explicit that screams (or whispers) its long history and glorious past, other than, perhaps, a side hall with P.O. boxes wall to wall -- They looked rather abandoned, and given the scarcity of customers I suspect they are but remnants of the past that proved too cumbersome to dismantle and remove, and were thus graciously left in place. Anyways, they appeared pretty ancient, and were quite fun to look at.

|

| Post office lobby looking surprisingly well-lit in this photo. I should probably get a Santa Hat too. |

|

| P.O. boxes wall to wall |

|

| A few "Keyless Lock Company" boxes at the station |

These very P.O. boxes you are now looking at drove me down a rabbit hole upon return, and here's what I found -- Some very similar-looking boxes (down to their star-shaped keyholes and etchings on all sides) are apparently for sale on eBay (what isn't?), and one seller is kind enough to mark them as products of a "Keyless Lock Company" in the 1950s. This catchy name has since been adopted by another, unrelated enterprise, but a website for safe bank collectors (I kid you not) tells me that the original KLC was organized in 1892 and soon became the leading keyless lock manufacturer in America, counting the Postal Service among its clients.

You might wonder, as I did too, why they are called "Keyless Locks" while having those really very conspicuous keyholes in the upper middle. Turns out said keyholes were a later addition -- Their original design features a knob in its place, which the user could turn to point at those alphabetical letters (A to J) on each "spike" of the star. Presumably patrons found it more challenging to memorize combinations than to keep tangible keys (given how often I resort to "Forgot your password?" I cannot blame them), and had them re-worked to accomodate. I should also note that these antique boxes aren't too expensive to come by ($65 for one plus its combination), I might actually get one and try it out.

The Union Station Branch

And we're getting off-topic. With the first job well done I marched across 1st St NW and headed into the Union Station. Its post office is located one ground below, obviously new by post office standards, and really not much to look at. I should probably have stayed a little while longer to get an ice-cream, a sandwich or some other snack from the many shops in the Station, but anxious to complete my intended triathlon of the day, I deposited the second envelope, snapped the photo below, and promptly left.

|

| The Union Station branch. Say hi to the snowman -- and the lady behind the counter of course. |

The Frances Perkins Branch

This rush of mine was, at least in part, driven by the worries that I would run into some troubles at the third station, which is located in the Department of Labor and aptly named after its 4th and longest-serving Secretary, Frances Perkins. I was imagining security checks, guards asking me what I am there for, me saying "to go to the post office" and them replying "use a civilian branch" or whatnot. In the end, the first three did happen, but their response was just an amused "okay" and, upon checking my ID and handing me a piece of paper permit, I was in the Frances Perkins building sending my third letter from the Frances Perkins branch.

|

| Front entrance to the Frances Perkins building, but I had to use, naturally, the visitor's entrance |

|

| The Frances Perkins station, photo taken minutes after it closed for the day |

|

| Labor Day Stamp (1956) |

To my surprise, this unassuming post office wasn't the only postal element there. There were three more: First was a panel of stamps featuring Perkins issued in 1980; second was a seal of the National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC), the foremost labor union for postal workers, hung on a wall alongside several other major labor organizations. Finally there was this enlarged 1956

commemorative stamp -- Its powerful design came from a mural called "Labor is Life" at the DC headquarters of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), created by artist Lumen Martin Winter who also worked on the interior of United Nations General Assembly Building in New York City. Also open for me to roam around in was a large lecture hall with portraits of past Secretaries of Labor, but no coffee could be had as the small eatery behind reception was closed at the time.

The National Association of Letter Carriers

|

Either a supremely boring design or the pinnacle of simplicity.

Don't the birds look ominous? |

I should also mention that, en route to the Department I passed the headquarters of NALC, which can best be described as a gigantic white slab with square windows. But I cannot wholeheartedly put my heart against this building as it is simultaneously so sublimely imposing that you can hardly ever erase it from your memory. There isn't much to say about it because I wasn't able to visit (yet), but the NALC does have an online shop where you can spend $85 on a podium seal. Although becoming its spokesman isn't in my career plan, I did find a few intriguing items, including such excitingly named publications as National Agreement Between NALC & USPS or Joint Contract Administration Manual. I will probably get the former and see what the deal is all about.

Still, not too bad for my first day as a self-proclaimed postal pilgrim. Hopefully those to follow would be as fruitful and, perhaps, when I get my letters I may see on them those circular thingies they call postmarks.